I travel to learn with my hands—by touching the warp and weft, by watching how a drape is coaxed into place, by listening to the quiet stories that cloth carries. As a culture travel curator and textile enthusiast, I’ve long been enthralled by the poetry of unstitched garments. In a world ruled by seams, zippers, and speed, these fluid textiles feel like a deep breath—timeless, adaptable, and intimately human. When I attended the Nyokum festival earlier this year it sent me back to my field notes on Northeast India, where unstitched garments are more than attire. They’re living archives of identity, resilience, and design intelligence.

Unstitched garments are the original slow fashion: minimal waste, maximal meaning. A single length of cloth can be restyled, passed down, repaired, and revered. It carries memory in its threads — of who wove it, for whom, and why. In Northeast India, every tribe and community speaks a distinct visual language through color, motif, and drape. The fabric tells you where someone is from, what they value, and sometimes even their role in a ceremony. And the beauty lies not only in how these textiles look, but in how they are worn—how they move with the body, how they adapt to terrain and climate, how they honor both modesty and expression.

Arunachal Pradesh: The Nyishi’s fluent drape

In Nyishi communities, I watched a choreography of cloth—drapes that looked effortless but carried finely tuned codes of belonging. The genius is in the balance: a wrap that keeps you warm in a mist-laced valley morning, yet frees the limbs for daily work. Subtle differences in how a corner is folded or a border is displayed can signal generational knowledge. What struck me most was the drape’s dialogue with the wearer—never rigid, always responsive. No two people wear the same length of cloth identically, which means individuality is not only allowed; it’s celebrated. The result is a form that feels modern without trying: sculptural silhouettes, clean lines, and organic texture that would thrill any designer obsessed with cut and fall.

Assam: The Bodo dokhona and its many lives

In Assam, among Bodo communities, I fell for the dokhona (often spelled dhokhon)—a seamless wrap that’s as eloquent as any stitched ensemble. Women drape the dokhona around the waist and chest, often with variations that play with coverage and emphasis: pleated across the bust for ceremonial dignity, closely wrapped for daily ease, or styled to showcase the agor (woven motifs) along the border. Paired with the jwmgra (scarf) and the ceremonial aronai, the dokhona becomes a complete language: geometry, color, and proportion in conversation with movement.

What makes the dokhona remarkable is its adaptability. I watched elders secure it with a quiet precision born of habit, while younger women experimented—cinching a waist, letting the border fall asymmetrically, or pulling the drape slightly higher to frame jewelry. The cloth itself, often handwoven in bright yet grounded palettes, carries motifs inspired by nature—flowers, creepers, and stars—endlessly recomposed. A single dokhona can traverse a lifetime: everyday wrap, festive attire, heirloom. It’s the kind of garment that teaches you how to wear it, asking only that you listen.

Nagaland: The eloquence of shawls and Mekhalas

Nagaland’s shawls are perhaps the most instantly recognizable textiles of the region—bold, graphic, and storied. Black, red, and white form a chromatic trinity that reads as both classic and strikingly contemporary. Historically, certain arrangements of stripes and motifs once spoke of warrior prestige or community affiliation. The beauty of a Naga shawl is how it performs: over the shoulder in layered folds that create sculptural volume; wrapped close against the cold; or unfurled as a visual statement in a procession.Today, those codes are honored without re-enacting the past, and the textiles remain the heartbeat of ceremony and identity.

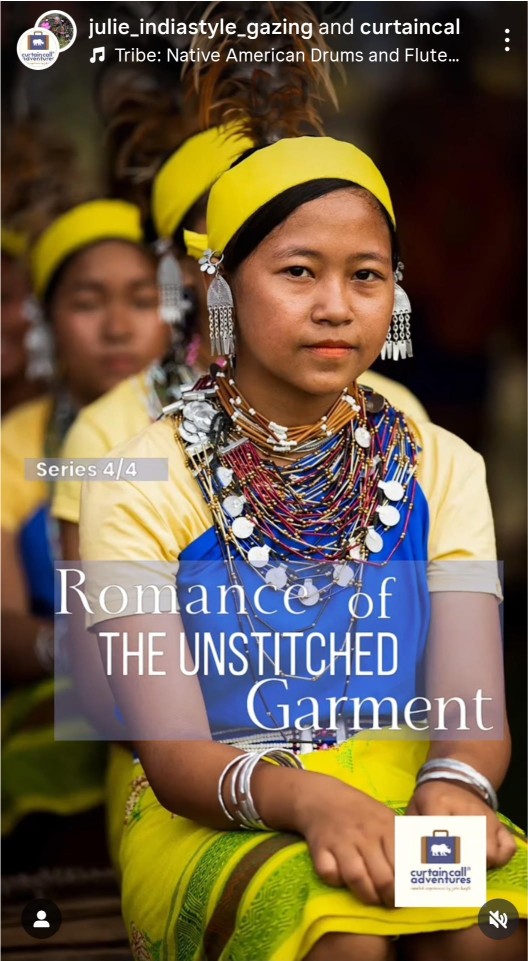

Meghalaya: Movement at Wangala

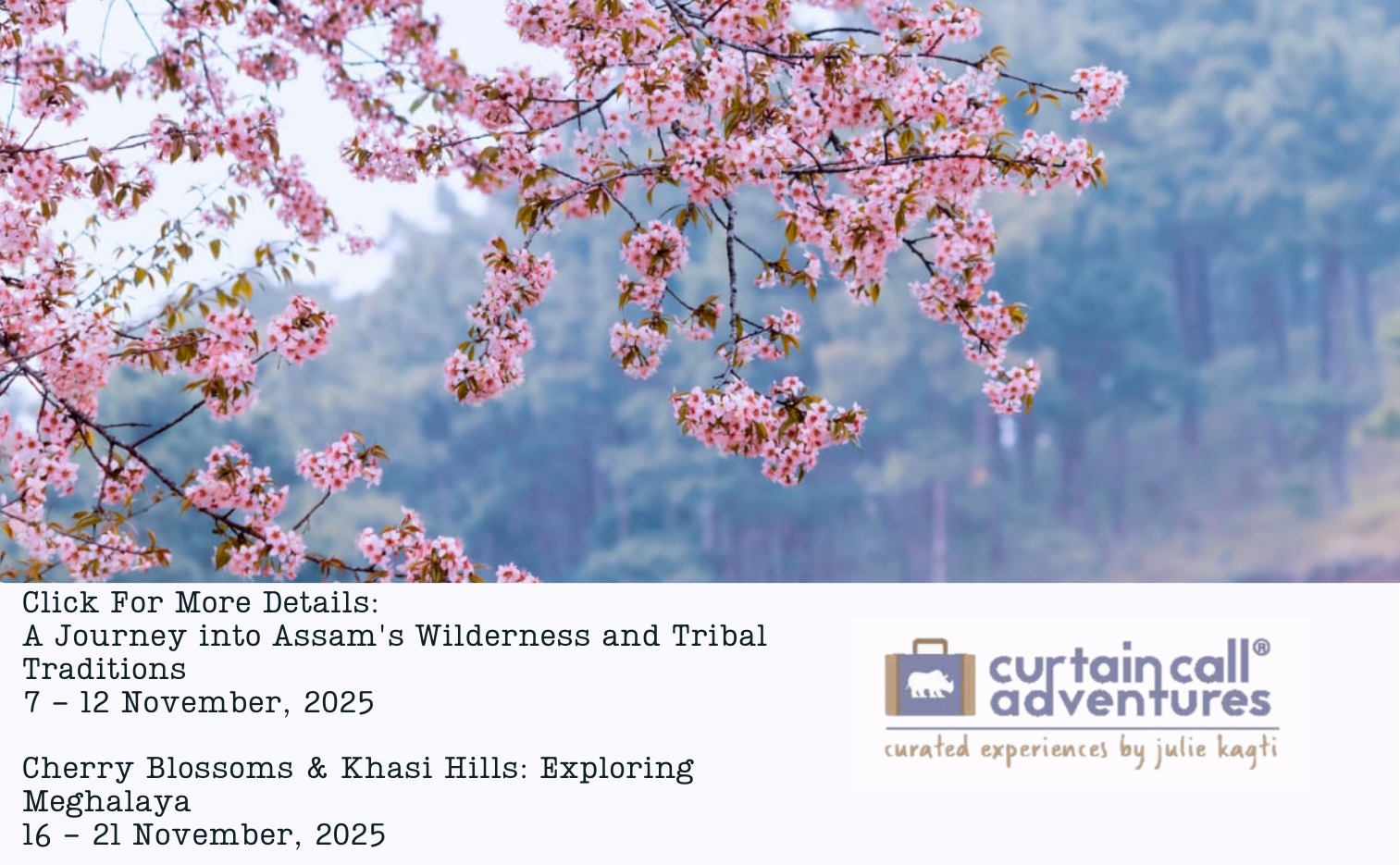

In Meghalaya’s Garo Hills, I timed a visit with the Wangala festival—drumming that thrums in your bones, dancers slicing arcs through the air, and textiles moving like extensions of breath. Unstitched wraps and shawls come alive here. Their ease is practical—they allow full range of motion for vigorous steps—but they also heighten the spectacle. Color becomes cadence; pattern reads as rhythm. The camera loves these garments because they love motion: you see the surface design, then you see how it transforms as it ripples. That dynamism is the heart of unstitched clothing. It’s never static; it performs with you.

Why unstitched still matters

Each stop on this journey revealed the same quiet truth: unstitched garments solve for climate, culture, and craft in ways that today’s fashion often overcomplicates. They are:

– Modular: one cloth, many lives.

– Repairable: a loose thread is a conversation, not a crisis.

– Size-fluid: bodies change; the drape adapts.

– Low waste: no cutting table offcuts, no pattern-piece puzzles.

Designers search for forms that are both new and timeless. The North East offers a blueprint hiding in plain sight: cut less, understand the body more; let gravity, grain, and gesture do the tailoring. The drape is the design. And when you look closely at a Bodo dokhona’s border placement, a Nyishi wrap’s considered fold, or a Naga shawl’s visual weight, you see a sophistication that rivals any avant-garde runway.

Field notes, then and now

My Instagram Reels on ‘ The Romance of The Unstitched Garment’ — short, sensorial windows—echoed moments from my notebooks: a weaver in Assam counting threads under her breath; a Naga lady adjusting her Mekhala so; Garo dancers laughing as a gust lifts a corner of a wrap and they tuck it back mid-step without missing a beat. Technology may accelerate how these images travel, but the garments themselves resist haste. They ask you to slow down, to practice the drape until your hands remember it, to understand that style here is not an accessory to identity—it is identity, worn.

Bridging tradition and modernity

I often style these textiles in contemporary contexts—pairing a Naga shawl with a crisp shirt, draping a dokhona as an evening column, wrapping a Nyishi-inspired length over wide-leg trousers. Each time, the garment recalibrates me: stand taller, move with intention, let the fabric lead. For travelers and fashion lovers alike, these pieces are invitations to dress with awareness. I hope more people will be inspired by these drapes.

The romance for these unstitched garments of Northeast India is not nostalgia; it’s a living practice of beauty and sense. From the sculptural calm of Nyishi drapes to the versatile eloquence of Naga shawls, and the many-lived Bodo dokhona with its expressive borders, to the kinetic joy of Wangala’s festival wraps—each cloth is a chapter in a collective epic. If fast fashion is volume without voice, these textiles are melody—memorable, portable, sung in many keys.

I carry that melody with me. Every time I fold, wrap, and let a border fall just so, I’m reminded that the best garments don’t just fit the body—they fit a way of being in the world. One drape at a time.