Article by Prerana Choudhury

Manipur, one of the seven northeastern states of India, is a picturesque region covered by hills, plains, lakes, and forests. A historically and culturally rich state, Manipur prides itself on its diversity. It is home to numerous tribes and indigenous communities, and has a rich repository of performance arts, dances, rituals, and festivals. The region is packed with biodiversity, much to a traveller’s delight. Whether you are a history buff, a performer, a textile professional, or a wildlife enthusiast and birdwatcher, Manipur has a way of quietly entering your heart and refusing to let go until you visit the place again.

The region is bordered by Nagaland to the north, Assam to the west, Mizoram to the southwest, and the country of Myanmar (Burma) to the south and east. The dense and diverse topography lends her an exquisite beauty that makes even a simple road trip replete with delight. Undulating hills and vast expanses of green are a constant companion along with a clear, blue sky – things we city people miss out on and relish with great joy on our travel breaks.

Jawaharlal Nehru once described the state as the ‘Jewel of India’ and he got it right. Physically, Manipur comprises of two parts, the hills and the valley, each with its distinct set of cultures. The hills cover a major portion of the land (about 9/10) while the valley is situated in the midst of the hills. Manipur Valley is about 790 metres above sea level. Some of the major rivers that flow through the region are Iril, Nambul, Sekmai, Chakpi, Thoubal, and Khuga.

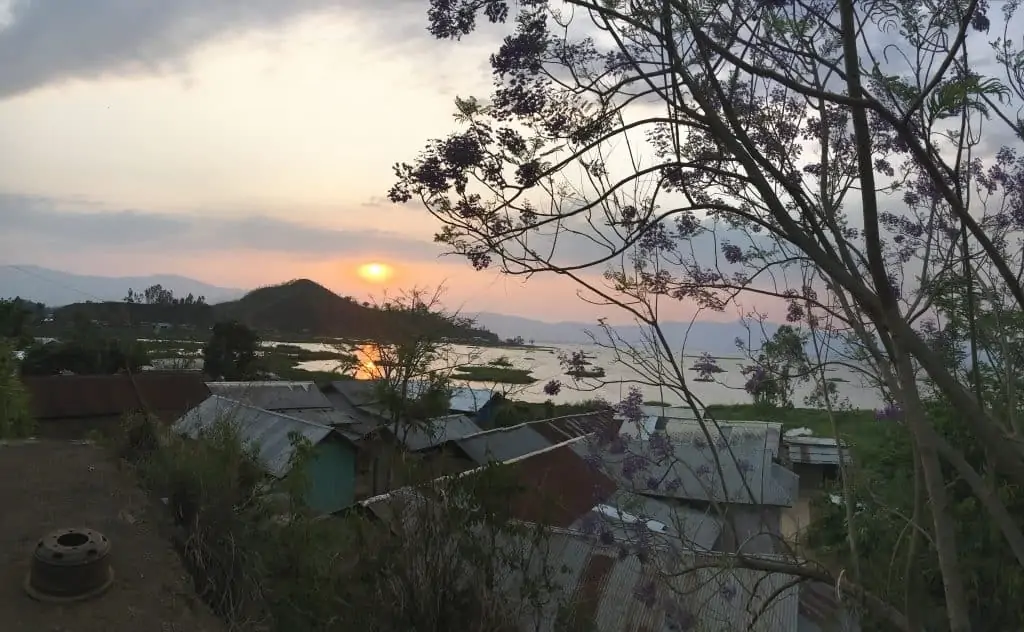

Manipur also consists of the fascinating Loktak Lake, the largest fresh water lake in northeast India. It is very much like an inland sea, with small islands where people reside.

Manipur is comprised of the Indo-Mongoloid group of people known traditionally as the Kiratas. In the hills reside two major groups of people, the Nagas and the Kuki-Chin-Mizos, who are further comprised of various groups and clans. The valley, on the other hand, has become a melting pot of people and cultures with almost all of the original (seven) clans assimilated within the dominant Meitei community. The history of the Meitei people is still largely obscure but the general conjecture is that they are descendants of the Tai people, who entered the Manipur Valley and interacted and merged with the local people. The valley, located strategically, became the crossroads of trade between Manipur and Burma, and hence an active place of breeding Indo-Burmese culture.

Like the rest of the Northeastern states, Manipur is a culturally rich spot of handloom textiles and performance arts, both of which interact with each other in significant ways. At the same time, handwoven textiles form a major component of domestic life of Manipuri women, most of whom are expert weavers and start learning the art from the tender age of ten. The tradition of weaving is both a socio-cultural and a spiritual practice of the women of the region, and it has existed since time immemorial.

A close observation and study of traditional motifs will reveal how the weaving practice is closely tied to nature and the world of flora and fauna. The lamthang khut-hat and lindo mayek, for instance, are ‘snake motifs’ and borrowed from the animal world. Similar motifs include the Sangai (a deer design), wahong (a peacock motif), shami-lami phi, and ningkham khoi mayek. Floral motifs, once extremely sought after, reflect an old world charm in today’s time. These include the kundo (jasmine), attargulab (rose), and leihao (champa), very common in the earlier days.

Today, like in the rest of Northeast India if not the entire country, motifs are being modified from the original traditional ones or recreated entirely to suit modern taste and market demands. Such a phenomenon has caused traditional motifs to disappear from contemporary fabrics and textiles so much so that the younger generation of weavers are not quite familiar with them. This creates a gap between two generations of weavers and their aesthetic taste or preferences. The older generation continues to harbour a sense of nostalgia, inclined towards the preservation of old ways, while the new generation weavers cater to contemporary tastes. This raises important questions for the preservation of textile heritage of a region or community; one cannot, after all, ignore the role of textiles in influencing narratives of material culture and history.

When we speak of Manipuri textile, what comes to mind immediately is the ethereal moirangphee. In a way, the moirangphee has become synonymous with Manipuri weaving/fabric and has found a surge of popularity across the country in the form of sarees. The fabric, woven traditionally of silk and cotton, has dreamlike quality that reminds us of characters from folklore. It originates in Moirang of Bishnupur district – hence the term ‘moirangphee’ (‘phee’ in Manipuri means cloth). The moirangphee is traditionally worn on the upper part of the body while the lower garment or loin cloth is called the phanek (it is worn like a sarong).

Weaving, like performance arts, rituals, and festivals, comprise the vast repertoire of living traditions of a people. It has been practised across eras and generations, and passed down within families and communities primarily from women to women. The loom was an integral part of a woman’s life; it was traditionally given as part of dowry so that she could continue weaving for herself as well as for her family members. A woman who could weave – which almost everyone could, and did – was looked upon with immense respect. It brought her great social stature.

Weaving continues to exist till today as their traditional and ‘time-honoured occupation’. It also provides the largest employment to women after agriculture and thrives as a cottage industry.

Although the onslaught of power loom broke a certain rhythm of life and structure centred on the hand loom, a fresh wave of handloom enthusiasm has been sweeping the country in the current times, thanks to the changing dialogues and perspectives within the fashion industry. There has been a shift of aesthetic in consumer culture, causing the urban crowd to become more aware and sensitive about consumption practices by asking the right questions (Fashion Revolution’s question/slogan ‘Who Made My Clothes?’ brought the right amount of attention to an issue kept in darkness for far too long). The word ‘sustainability’ may have become a buzzword and overkill in recent times but one cannot deny the positive impact created by designers, entrepeneurs, weavers, and curators on the block to make ethical consumption popular and savvy.

It will be pertinent to mention about the Langei Project in this context. 42-year old Telem Arunkumar, a native of Nongpok Sanjenbam village, 15 kilometres from the capital city of Imphal, started the project as an effort towards sustainable development and rural livelihood for the (near about) 500 people in his village. It spreads across ten acres of land and comprises of a weaving centre for the women and a poultry farm that employs the men. The weaving centre consists of about 150 traditional looms and produces close to 40 phaneks daily. The initiative not only creates a regular source of income for the women but also helps in the preservation of weaving, of a tradition negatively impacted by the prominence of the power loom and mass-produced clothes.

Socially rooted enterprises such as this are a step in the right direction. They keep hope alive.

Written by: Prerana Choudhury (Instagram: @starr_e_nightt)

One Response

I want learn manipur weaving