Says Morningstar Khongthaw who is keeping a centuries-old tradition alive by raising awareness about Meghalaya’s famous living root bridges

Last month, James K Sangma, a cabinet minister from Meghalaya, proudly tweeted how Meghalaya’s Jingkieng Jri or living root bridges had been included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site tentative list. These bridges are a testament to the marvel of nature and the ingenuity of the Khasi community – one of the main tribal communities in the region who have been credited with building these bridges. Given that some of these living root bridges date back to a few centuries and there is no manual record of how they’ve been built, it’s amazing to discover that most of this knowledge has been passed down through oral tradition.

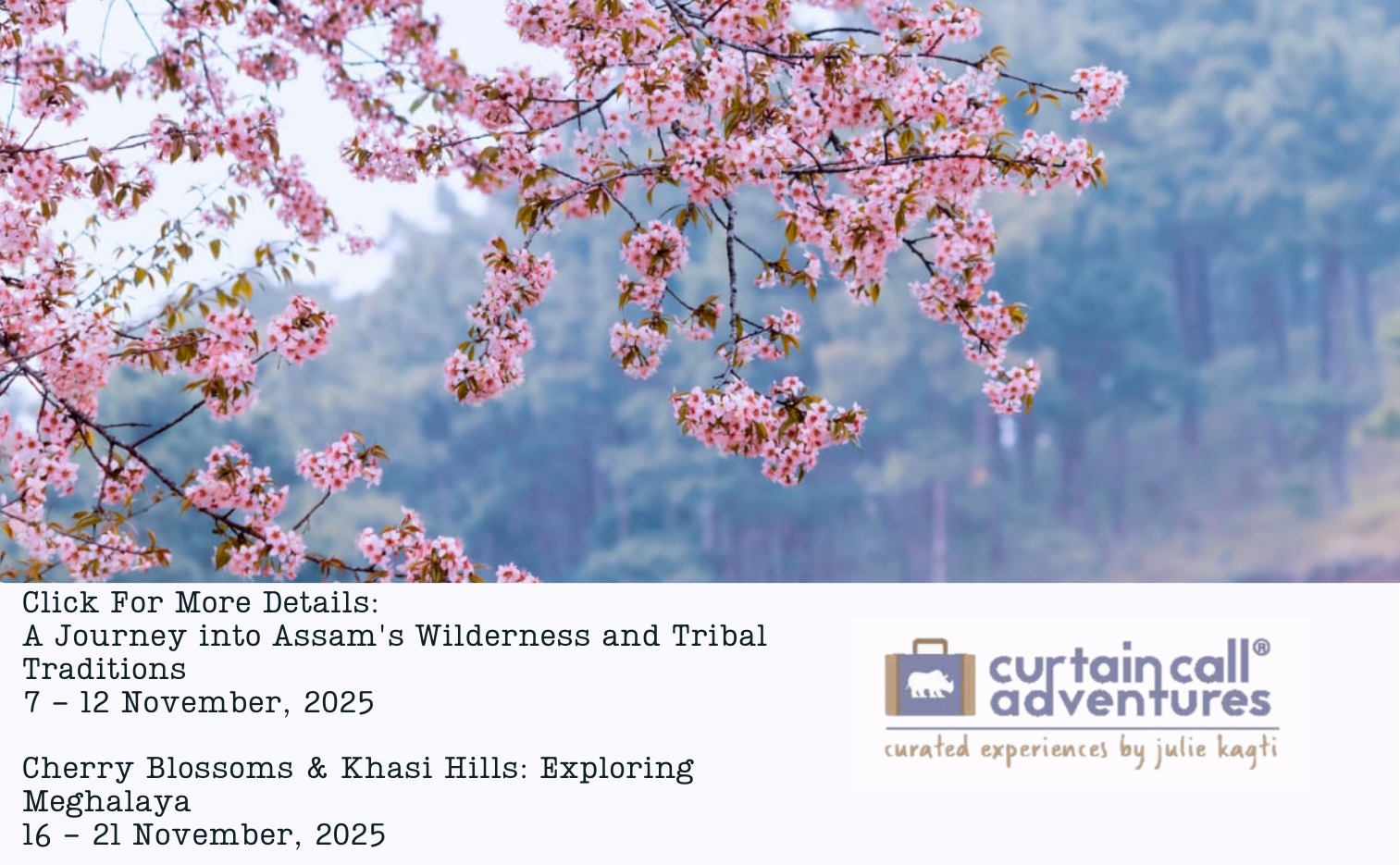

Home to over 100 such bridges found across 70-odd villages, these bridges were built out of necessity. Living in remote locations with little to no access to proper roads, villagers often had to traverse through dense forested lands and find their way across rivers that would swell up dangerously during the incessant monsoons that Meghalaya is known for. Taking advantage of the massive aerial roots of the Ficus elastica – a tree that grows abundantly in Meghalaya – the villagers found a way of manipulating these strong yet elastic roots to form a bridge-like structure over time. Typically, a bamboo or wooden scaffolding is built connecting the two ends of river bank and the roots of the tree are guided through it; over time, they naturally intertwine and bond forming a strong mesh-like structure.

Gradually, however, some of these oral traditions have been lost as the younger generation of Khasis move to urban centres in pursuit of higher education and job opportunities. The bridges have to be maintained and looked after in order to ensure that they remain stable and traversable. Realising the importance of this, Morningstar Khongthaw, 26, a native of Rangthylliang village, has become a champion of living root bridges creating awareness both within the community as well as among outsiders. The self- proclaimed “living root bridge activist” launched the Living Bridge Foundation in 2018. Since then, LBF has grown to 16 members who work on voluntary basis. From looking for bridges that need to be revived to raising awareness among villagers on why they need to keep this tradition alive, LBF has a varied agenda.

In fact, Morningstar was in a village in West Garo Hills when we caught up with him over a call. Unlike the Khasis, the Garos do not have a tradition of building living bridges and Morningstar was called in to identify the potential of building a bridge in the area. “First we will need to inspect the site and then involve the local chief of the village for permission to start constructing the bridge,” he says. Given that it takes 20 years or more for a living bridge to develop, it takes great commitment to see the process through. This is also the reason why it takes an entire village (almost!) to raise a bridge. But given that eco-friendly living bridges can outlast several generations and are not liable to get washed away in a flood, it’s more than worth the trouble.

Morningstar was only 16 when he decided to drop out of school and pursue fulltime his passion for building and restoring living bridges. His decision wasn’t met with much enthusiasm from his family. “My mother, especially, had hopes that I would go on to become a doctor or engineer. She wouldn’t speak to me for a long time,” he recalls. It was only after researchers and tourists started visiting their village and Morningstar requested his mother to host their guests that she started taking his work more seriously. His primary source of income is from working as a local guide. “Fifty per cent of my earnings go into the funds for LBF and to organise community programmes,” he claims. In 2021, the Meghalaya government also contributed funds for the first time to the foundation in support of their Hands on Roots initiative through which they continue to raise awareness among villages as well as restore neglected bridges. Donations have also come in from friends and well-wishers including the Technical University of Munich. Researchers from the university have been studying these living bridges for several years now in an effort to understand living architecture and how it can translate into the contemporary urban context.

Tourism has been a double-edged sword for the continuance of living bridges. While it encourages locals to preserve the bridges in order to attract more visitors, uncontrolled tourist footfalls have also had an adverse effect. “In certain places like the double decker bridge (in Nongriat) there’s a continuous flow of tourists. These bridges are ecologically sensitive. With hundreds of people constantly stepping on their roots, they start withering and drying up. That’s why sustainable and responsible living bridge tourism is a must,” Morningstar explains.

For that, Morningstar has plans to set up a Centre of Knowledge for Living Architecture near his village. “Our hope is to build a homestay where tourists can live and interact with the elders of our village to understand how living bridges work. It’s not just about coming to the bridge taking a selfie and leaving,” he adds. Interestingly, Morningstar also owns a 600-year-old ficus tree situated about an hour’s walk away from his village. “It belonged to an 85- year-old elder who was going to allow it to be cut down. But I met him and built my case, pointing out how the tree had supported two bridges. So he handed the tree over to my care,” says Morningstar who has also built a treehouse atop it.

With renewed interest in the preservation of living bridges, the future is looking bright for these marvels of nature. For visitors to Meghalaya, visiting these living bridges and meeting the elders who have nurtured them, is worth the trek.